Rick Suhr had a policy. He wasn't going to coach or train female athletes.

It's not that he believed young women shouldn't be coached in track and field or any other sport for that matter. He just didn't believe he was the person to do it.

Suhr admits that, when he subscribed to this policy, he was like many young coaches who think they are better, brighter and more knowledgeable than they actually are. So whenever Suhr, who was a former New York State wrestling champion making a name for himself as a pole vaulting coach in the late 1990s, was approached and asked to coach girls, he simply said no.

Imagine what would have happened had Suhr stuck to his policy. The face of high school girls pole vaulting in New York State would likely look decidedly different today and the revolution the sport experienced in the early 2000s might never have taken place. The records set and broken and reset again by the likes of Jenn O'Neil and Mary Saxer and Tiffany Maskulinski might never have come to pass had Suhr not changed his mind.

"I just didn't want to train women," Suhr, 52, said. "And I told everyone that. I trained wrestlers and football players and male pole vaulters. I told them I just don't train girls. I didn't know how to train girls. I grew up wrestling and I didn't know how girls were going to react to the stress of me coaching them the way I know how to coach. I came out of a wrestling program that was very Spartan and I didn't even know how to start coaching girls so I avoided it for three or four years.

"I got asked in 1998 and I said no. By 2000 I was having some local success and I scurrying around trying to win Counties and then Sectionals and then States. I was having guys go to the State meet and finish third or fourth. And I kept thinking I have to have a State champion. But I had, at the time, what I call young coaches syndrome - I thought I knew so much more than I knew."

Suhr, however, would soon find out that he did know so much more than he could have ever imagined as he and a group of young women started a revolution that continues to keep the world of New York State track and field buzzing nearly two decades later.

IN THE BEGINNING

The first significant female prep pole vaulter in New York State was Mt. Sinai High School's Amy Linnen, who first broke 12 feet to win the state crown as a junior in 1999, the year after the pole vault had become an official girls event in New York. She had her sights set on repeating in 2000 as a senior and she did just that, taking home the title.

That was a moment that Suhr, who was coaching at that state championship meet, hasn't forgotten.

"I remember them announcing that she was trying to break the State record," Suhr said. "At the exact same time they made an announcement about a girl running in the pentathlon who was also trying for a state record and it was the first year that she was running track. I thought, we have two really good athletes here."

"I remember them announcing that she was trying to break the State record," Suhr said. "At the exact same time they made an announcement about a girl running in the pentathlon who was also trying for a state record and it was the first year that she was running track. I thought, we have two really good athletes here."

The two athletes were Linnen and Fredonia High's Jenn Stuczynski, who won that pentathlon years before she ever thought of pole vaulting. She wouldn't begin vaulting until she was 22 years and would be coached by Suhr. Eventually Suhr and Stuczynski got married and she went on to set many world records and win an Olympic gold medal. Jenn Suhr is still vaulting at the age of 38.

Linnen would win the Foot Locker National Championships a week after Rick Suhr first heard her name, becoming the first New York State girl to vault over the 13-foot mark [13-0.25]. Though he never coached Linnen, he did appreciate what she had done.

Suhr, who had built a facility at his home and was training male pole vaulters, eventually softened on his stance regarding coaching female athletes. He had called his old wrestling coach for advice and he simply told Suhr to "train her like a guy".

"I was expecting some great far out advice," Suhr said. "So there I was. I won't ever forget it. I went into the building, set up a lawn chair and sat down and there I was training someone, just training her like a male pole vaulter. I thought if it works out, it works out and it worked out."

Maskulinski, who attended Iroquois High School, was Suhr's first big-time success with a female vaulter. She went to Suhr following her freshman year, during which she tried to teach herself how to vault. She had been watching videos and going to camps "trying to learn the best" she could.

Maskulinski, who attended Iroquois High School, was Suhr's first big-time success with a female vaulter. She went to Suhr following her freshman year, during which she tried to teach herself how to vault. She had been watching videos and going to camps "trying to learn the best" she could.

"I tried to teach myself how to bend the pole and it was a disaster," Maskulinski, whose married name is Regdos. "Eventually I broke my collarbone trying. A friend of mine heard about Rick Suhr and said I should look into one of his camps, so I did. After the camp, he said why don't you stay and we'll work on a few more drills. I kept going consistently from there."

"I knew I wanted to jump higher, I just didn't know how to do it. I could tell right away that Rick believed in what I was doing. I soaked up as much as I could that weekend. He told me he didn't think I could jump real high but we'll see what happens. I don't know if he had any real expectations until after I jumped 12 feet. Rick started thinking we could jump higher and go for a national record but not at first."

Suhr labeled Maskulinski as a breakthrough for him as coach. He began working with her in earnest and in the summer of 2003 she rewarded his faith with a victory in The Empire State Games. Maskulinski, with Suhr's guidance, refined her technique to a point where she was poised for a big 2003-04 junior year.

THE BREAKTHROUGH YEAR

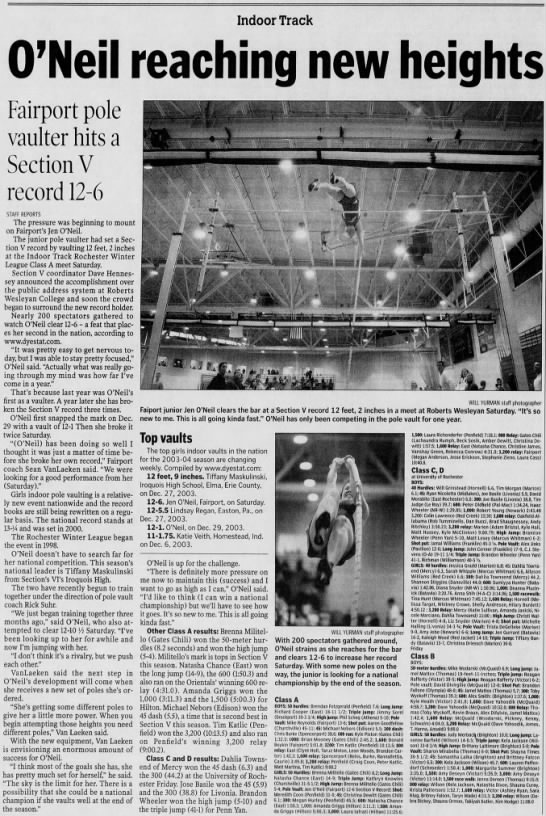

O'Neil also joined the pole-vaulting fold during her junior year at Fairport High, having showed some moxie during the spring of her sophomore season. She had come to track following a lengthy involvement in gymnastics, one that ended with her suffering a fractured spine when she was 15. She was paralyzed from the waist down for six months and there was a 50-50 chance she wouldn't walk again.

Yet, O'Neil persevered and, after fusion surgery on her back, slowly worked her way back to good health. She still wanted to compete, though, and during the spring of her sophomore year she joined the track team.

"Running around the track was low stress and I was able to keep moving," O'Neil said. "Midway through the season we were in the middle of a meet and the coach said we needed points. He heard I was a gymnast so he asked if I could try the pole vault.

"He hands me this giant pole, made for a man that weighs 180 pounds. I think I made it over seven feet in that meet and tried to get us a few points at every meet after that. That summer I heard about Rick Suhr and the training he was doing at a two-day weekend intensive camp. He took me on that indoor season and a few months later I was upward of 12 feet for a Section 5 record. It was less than a year where things just clicked into place."

Saxer, who was also a gymnast, would join the group as well that summer having never tried pole vaulting before her junior year of high school [2003-04]. She says she didn't have interest in the event and was focused on her long jumping. In fact, she was working on her long jumping at a camp hosted by Suhr and he approached her several times the first day, inquiring as to whether she would like to vault.

Saxer, who was also a gymnast, would join the group as well that summer having never tried pole vaulting before her junior year of high school [2003-04]. She says she didn't have interest in the event and was focused on her long jumping. In fact, she was working on her long jumping at a camp hosted by Suhr and he approached her several times the first day, inquiring as to whether she would like to vault.

"He kept bringing it up but I was saying 'Nah, I don't have any interest'," said Saxer, 32, who went to Lancaster High. "The second day of the camp, though, sure enough there I was with the pole vaulters trying to pole vault for the first time. It just kind of took off from there. In a lot of ways, it was the perfect situation for me at that camp. Rick approached me, he was a great coach and I was in great hands right from the beginning.

"He had Tiff and Jenn O'Neil and Janice Keppler. The group they had formed was already having success at a high level so it was just the perfect setup. I never thought that it would have gone the way it [eventually] did. I started going a couple of days a week. I was the last one to join the main group of four and I was always the one trying to keep up, especially in the beginning."

The pieces were now in place for the revolution to begin. It became evident early on that Maskulinski was headed for a productive 2003-04 season She jumped 12-3 and then a nation-leading 12-9 in December before hitting 13 feet in January to break Linnen's state mark. She was not alone, though.

Saxer also had a big indoor season, jumping 11-3 to finish second in the state championships. She would finish second in the state in the outdoor season as well, vaulting 12-3. Maskulinski would take the state crown with a vault of 13-5 while O'Neil took third at 12-3, setting the stage for what would be a showdown at the Adidas Outdoor Championships in June.

"No one believed that they were jumping that high up here," Suhr said. "Tiffany had jumped over 13 feet a few times and they [critics down south] were saying that no way a 5-foot-3 girl was jumping 13-5. They truly believed that someone out of Buffalo couldn't jump that high. It fueled me that spring to justify her New York State championship.

"That's when I made the decision that we were going to drive 11 hours to North Carolina to see how good we were against these people who said they were better than us. So, I took it as a challenge. We piled into the car got there and said we were going to compete."

Saying that Suhr's charges were going to compete proved to be an understatement. Maskulinski jumped 13-1.5 to take the national championship. O'Neil also jumped 13-1.5 but finished second because she needed more attempts.

Saying that Suhr's charges were going to compete proved to be an understatement. Maskulinski jumped 13-1.5 to take the national championship. O'Neil also jumped 13-1.5 but finished second because she needed more attempts.

"It was a good time to have my highest height," O'Neil said. "I almost no heighted at that meet. My first attempt I blew through the pole. I'm from Rochester and I like the snow. It was 90 degrees and it was the weirdest thing. On my second attempt, my hands slipped all the way down the pole [from perspiration].

"I had one more attempt and thankfully we worked things out through talking and some changes. I went to that from almost having a no height."

Maskulinski was named the nation's top scholastic pole vaulter by Track and Field News. Her jump of 13-6 at the New York Western Track Series in June was a state record that would last less than a year before it was broken by Saxer. It remained the highest jump by a junior in New York for 15 years. Each of Suhr's trio was named All-American, proving once and for all that upstate New York was indeed a hotbed, one that was producing some of, if not the best, vaulters in the nation.

THEN CAME DARTMOUTH

The focal point of that season occurred on Jan. 8 at The Dartmouth Relays when Maskulinski and Saxer broke, set and broke the national record.

The focal point of that season occurred on Jan. 8 at The Dartmouth Relays when Maskulinski and Saxer broke, set and broke the national record.

It was a bitterly cold day as Suhr began his journey from upstate New York to Dartmouth. While he expected great things from his vaulters later that day he had more pressing matters at the day's outset.

"It was -2 degrees when I left my house and my driver's side window was broken," Suhr said. "I had to drive seven hours to Dartmouth with no window on the side of my car. But we drove all the way there and when we showed up, it was a huge deal for us. They said the building opened at 8 in the morning but the custodian agreed to open it early for us and we rolled in there at 6:30. It was freezing cold.

"I knew they could handle it, though. It's 17 degrees in my building and two weeks before that Mary jumped 14 feet there."

Maskulinski was the first to break the national record of 13-5 that day when she vaulted 13-5.5 on her first try. Saxer equaled the mark a few minutes later then cleared 13-7 and finally 14 feet to become the first United States high school girl to clear that mark.

"I had broken the previous national record a few weeks prior by a quarter of an inch or something and it kind of shocked me to be honest," Saxer said. "A few weeks later we went to Dartmouth with Rick and Tiffany there and I remember 427 being our hotel number. In metric terms, 4.27 meters is 14 feet. I was kind of in a foggy zone that day; everything was just clicking.

"I cleared the same height as Tiffany and we were both firing on all cylinders. Rick was saying go 14 feet and I cleared it on my second attempt. I remember it but at the time I was thinking 'Did that just happen?' There is a YouTube video of Tiffany and I from that day and I've watched it. It gives me chills. It's really cool."

THE US INDOOR CHAMPIONSHIPS AND BEYOND

That day at Dartmouth was the beginning of a whirlwind that impacted Rick Suhr, Saxer, Maskulinski and Jenn Suhr. His seniors were all but assured a place on any college team in the country while Suhr was becoming a nationally known vaulting guru. That reputation would only grow in February at the USA Indoor Championships.

Jenn Suhr had been working with Rick Suhr for only a few months and was still an unknown as the meet, which was held in Boston, began. She was a senior the year prior at Roberts Wesleyan College where she had been playing basketball in addition to running track. Jenn Suhr finished her basketball career as the school's all-time leading scorer but during the spring of her senior season, Rick Suhr was only concerned with her ability to jump. He approached her and asked her to try vaulting.

"I was 22 years old and the one time I went down to his facility, the girls were jumping so high and they were five years younger than me," Jenn Suhr said. "I was so embarrassed. I had graduated from college and here were these girls who weren't even seniors in high school and they were kicking my butt.

"I wasn't aware of the pole vault until I started. Once you start vaulting, the bug bites you quickly. It becomes very addicting. You want to get better."

Jenn Suhr would get better. Much better. Her world was about to explode in February of 2005 just a few weeks after Saxer had set the national mark at Dartmouth.

"Things really went crazy in February of 2005," Rick Suhr said. "They asked me to bring Mary to US Nationals. Mary wanted to go to her city qualifier and the state championships. I told the people running the meet that I might have someone better and they were laughing at me on the phone. But there I was two weeks later at US Nationals with Jenn."

Jenn Suhr didn't have a great start to the meet and by the midway point of the vaulting competition Rick Suhr was getting phone calls from the event's public relations staff.

"I'm thinking who is calling me in the middle of US Nationals while I'm coaching," he said. "Their PR person called and said hey, is that the girl you were talking about? I said yes that's the girl and I'm here trying to coach her."

Jenn Suhr, who entered the event unseeded and unknown, had only been vaulting for 10 months. Yet, she leapt 14-3 ¼ to win and stun the track world.

"She won it and it was probably the greatest upset ever," Rick Suhr said. "By the end of '05 we had the first two girls to break the 14-foot barrier in high school and that was huge at the time. We also had Jenn and she won the US championship. It's as crazy as you can get. As far as women's pole vaulting in New York State they had never seen anything like it, before or after."

.png)

The 2005 season was far from over, though. Saxer won the New York State Championship with a jump of 13 feet in the beginning of June. She captured the Nike National Championship two weeks later with a jump of 12-9.5. Maskulinski finished second in both events. She also jumped 12-9.5 at Nationals but finished second because Saxer had fewer misses.

Maskulinski, before heading off to Washington State University, competed at the Monroe County USATF Championships in early August and won that event with a 14-foot vault, still the Outdoor State Record. More on that run here.

JENN SUHR'S REMARKABLE RUN

Rick Suhr had stopped teaching following the 2003 academic year and by the end of the 2006 scholastic year he had given up coaching high school athletes in order to focus on coaching Jenn Suhr, whose remarkable breakout performance in 2005 set the stage for what continues to be a dominating career.

The amazing part about Jen Suhr's career is that it almost didn't happen and not because she didn't begin pole vaulting until she was 22. Suhr was a standout athlete in high school, starring on the softball team. She and the coach had a conflict, though, during her senior year and that led to her quitting the team and turning to track. She went on to win the aforementioned pentathlon and to run in college, all of which set up her working with Rick Suhr.

The work and the partnership paid off. Jenn Suhr, 38, has spent the better part of the last 14 years dominating the sport in a way no one else ever has. She took a silver medal in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing and followed that up with a gold medal four years later in the London Games. She earned a silver medal in Moscow in the 2013 World Championships and a gold medal in the 2016 Portland World Indoor Championships, setting a meet record with a vault of 16-3/4. Earlier that year she had broken her own world indoor record when she jumped 16-6.

"I wasn't aware of pole vaulting until I started but Rick was a student of the game and the history of the event," said Jenn Suhr, who married Rick in 2010. "He said you have to know about it and pay attention to it. Now I'm approaching 40 and the road I've taken is crazy. There were a lot of twists and turns that I wouldn't have expected.

"I never expected to still be going near 40 and still vaulting at competitive heights. It's not easy. Each year it gets harder and harder."

ERICA ELLIS LURES RICK SUHR BACK TO THE PREP RANKS

Former Gates Chili star Erica Ellis was an eighth-grader in 2015 when she first met Rick Suhr. She was determined to prove that she could be an elite pole vaulter - she had jumped 11-4 ¼, a then record for eighth-graders in New York State - and wanted to learn from the best. The problem was that Suhr spent much of the year in Texas and or coaching his wife. He hadn't trained a high school athlete in a decade.

"I run into her coach and he asks me to take a look at her and how she pole vaults," Suhr said. "I told him that I didn't train high school kids anymore but he said he only lived 15 minutes away, can I please take a look? I give in and her father brings her over on New Year's Day. Its 10 degrees in my building

"She comes in and she's tall and super thin. She was an 8-6 jumper when she came in. Next thing you know she goes on to become a 14-footer."

Ellis sent the prep pole-vaulting world into a frenzy in January of her junior year when she jumped 14-1 ¼ during the Akron Pole Vault Convention in Ohio. The height is recognized as the national record for high school juniors. She also holds the New York State sophomore record [13-3].

"She just accelerated as a junior," Suhr said. "I thought she might be the first 15 footer. We didn't work with her at all her senior year, though."

Suhr had moved down to his training facility in East Texas, in search of warmer weather. There, he would also work with local vaulters, working with a slew of female 14-footers in the Lone Star State.

Ellis, who is currently vaulting at Penn State, lost much of her senior year to injury. Although she managed to come back in the Spring, her season was shut down to focus on the College transition.

LOOKING BACK

All of the players involved in helping turn New York State into a girl's pole vaulting hotbed nearly 20 years ago look back at that time with great fondness, appreciating what they did more now than they did when it was happening.

All except for Jenn Suhr are retired. O'Neil went to Stanford but never got to jump for the Cardinal. Injuries and complications from her prior back problems forced her to give up the sport during her freshman year. She lives in Geneva, N.Y. with her husband and currently works at Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

All except for Jenn Suhr are retired. O'Neil went to Stanford but never got to jump for the Cardinal. Injuries and complications from her prior back problems forced her to give up the sport during her freshman year. She lives in Geneva, N.Y. with her husband and currently works at Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

"I went out on top," O'Neil said. "I only did it for two years but I got a lot out of those two years. I don't think I realized what we were doing at the time. I look back and I have to pinch myself. Out of the group of us, my name gets glossed over a little. I was the lowest vaulter out of all of us but in the grand scheme I jumped pretty high.

"I don't know if you can put a definition [or label] on it. I would have hoped I could be an inspiration for others that might be looking to vault. To say I was a pioneer, that would be cool."

.png) Saxer and her husband have an 18-month-old son and another one due in early July. She hasn't competed professionally since the fall of 2017. She believes that if "I get my butt in gear" she could probably get back into vaulting shape but she's enjoying motherhood far too much to be concerned with vaulting.

Saxer and her husband have an 18-month-old son and another one due in early July. She hasn't competed professionally since the fall of 2017. She believes that if "I get my butt in gear" she could probably get back into vaulting shape but she's enjoying motherhood far too much to be concerned with vaulting.

Still, she views her high school experience as the beginning of what was an incredible journey.

"It certainly was a special time," said Saxer said, who lives in northern Virginia. "I think I knew it at the time but I think I have more appreciation for that time in my life looking back at it then when I was in the moment. To be surrounded by all those young women, especially Tiffany, getting to go to meets together and constantly pushing each other. To be at that level in high school and have others right there alongside you was something else.

"I think now when I reflect on my journey that I was absolutely a pioneer. Breaking that 14-foot barrier and being part of that group was certainly special and unique.

Maskulinski, 33, lives in East Aurora, NY and is a successful physical therapist. She too is married and hasn't vaulted for "six or seven years". A shoulder injury during her final year of college kept her from training for a while but allowed her to focus on working to become a physical therapist and do some coaching. She ultimately got her advanced degree and gave up coaching as her career began to blossom.

Maskulinski, 33, lives in East Aurora, NY and is a successful physical therapist. She too is married and hasn't vaulted for "six or seven years". A shoulder injury during her final year of college kept her from training for a while but allowed her to focus on working to become a physical therapist and do some coaching. She ultimately got her advanced degree and gave up coaching as her career began to blossom.

"It's a very unique sport and you can't get the same feeling you get in general workouts as you do with the pole vault," Maskulinski said. "It was a part of my life that I really enjoyed and I took a lot from it. I enjoyed training with everyone and pushing everyone. It was intense but it was fun being around like-minded people. It was a cool experience."

Suhr, meanwhile, continues to have a successful coaching career. He views what he and this group of young women were able to accomplish with pride, not only because of what the girls achieved but for what he provided them.

"If you had told me in 2001 that I was going to train these girls and send them to college with great self-esteem and confidence and that they would have success and get to go to college for free, I never thought I would have had that kind of impact," he said. "There is no way that you can measure that kind of influence. All you have is the experience of witnessing seeing it done and have the gratification that you've seen it executed.

"It was a little scary sometimes but it worked out. Somehow I had enough tools in the tool box but I didn't know it at the time."

One that changed the face girl's pole vaulting in New York State.

- - Stories of the Time - -

Right Click -> View Image for full view

Democrat & Chronicle - Jan 11th, 2004